Japan Sake and Shochu Makers Association | JSS

Due to its overseas nickname of “rice wine”, people often conflate sake and sake production with wine culture. While the two share similarities, several aspects of their cultivation, production methods, and distinctive characteristics differ greatly. By comparing these traits, it becomes easier to understand and appreciate the uniqueness of sake.

Wine has a well-established reputation and cultural standing around the world. Sommeliers train for years to learn how to assess traits like aroma, astringency, and vintage discrepancies from the smallest sample. The familiarity of wine in casual settings even gives amateurs some insight into these qualities and how they emerge through the winemaking process.

Wine itself comes from fermenting grapes. Cultivating grapes, called viticulture, can pose several challenges, such as wildlife, pests, mildew, and soil management. Each variety of grape also has its own optimal climate and soil conditions that must be met for the best yield. After growing, the fruit itself is prone to damage from improper handling and other transportation hazards. To avoid grape loss, winemakers often produce wine close to or at the same location as cultivation. This close proximity of vineyards and wineries led to the development of “wine countries”, regions more suited to viticulture and winemaking by extension.

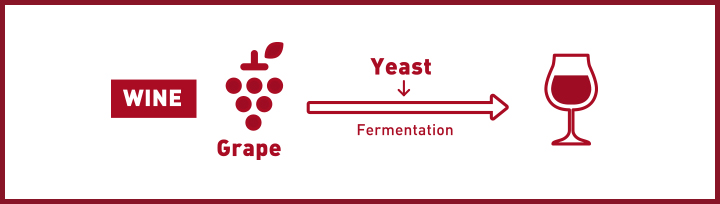

The winemaking process itself is relatively straightforward. There are four basic steps: harvest, fermentation, racking, and aging. After harvest, crushed grapes or the juice from pressed grapes begins fermenting after the introduction of a yeast starter. Next, winemakers transfer the wine between vessels in a process called racking to separate wine from other particles. The wine then ages for anywhere from a few months to several years before commercial sale and consumption.

Red wine and white wine go through slightly different production processes. White wine comes from the fermentation of juices pressed usually from green grapes with no remaining skins or pulp. Red wine derives both its color and tannin content from grape skins and pulp. As a result, a mix of grape skin, pulp, and juice are used in red wine production.

Some wine undergoes the process of malolactic fermentation. Malolactic fermentation is a process in which malic acid is converted into lactic acid by introducing lactic acid bacteria into the mix. Red wine often undergoes a higher rate of malolactic fermentation to lessen its naturally higher levels of acidity.

An important element of wine is aroma. The aroma itself mostly comes from the grapes themselves. Different varieties of grapes have their own distinct qualities that influence the final aroma. However, other factors also play a part in aroma creation. The yeast used and the fermentation process can affect aroma. Malolactic fermentation in particular can change the flavor by affecting sourness and acidity levels. Aging can also influence scent, especially if done in oak barrels.

As mentioned earlier, grapes are the most influential component of wine and each variety carries its own distinct characteristics. Additionally, the quality of the grapes determines the overall quality of the wine. Each grape variety has a different set of ideal growing conditions. But, generally, grapes require aerated, loose soil with good drainage and moderate levels of fertility. Farmers will also practice “fruit thinning”, or removing grapes from each cluster. Fewer grapes on a cluster create more sugar in each grape, which leads to higher alcohol produced in fermentation and higher quality wine in some cases.

According to convention, certain characteristics weigh more heavily than others in assessing wine quality. Ultimately, assessing wine depends on judging ideal traits unique to certain varieties. These varieties, such as chardonnay or merlot, correlate directly to the grape variety used. This places more emphasis on crop and growing conditions in creating wine varieties than changes in wine making methods. Since different varieties favor different growing conditions, there is a strong association between location and varietal quality. This establishes important geographic meaning and regionality within the wine community.

Aging can also play a crucial role in determining wine class. Most wines in commercial sales only deepen in flavor for roughly a year of aging. However, a small percentage of grapes produce wine with a flavor that improves after aging over several years, creating a very high-class wine. On the other hand, some wine is classed based on the short production process, such as Nouveau wines sold the same year the grapes are harvested.

In contrast with wine, sake has a relatively mysterious and simplified reputation outside of its home country, Japan. Very few sake experts live outside of Japan and the average consumer usually associates the drink with Japanese restaurants. As a result, the important flavor elements, production methods, and variety diversity often go unnoticed in regular sales. These crucial factors are important to understand when navigating the nuanced difference between sake and wine.

The three ingredients used in sake productions are rice, water, and koji. Rice crops require specific conditions to flourish. However, rice grains themselves are very easy to store and transport long distances. As a result, brewery locations are not dependent on rice cultivation. Instead, the presence of quality water is crucial for establishing a sake brewery. The level of water hardness and mineral content can affect the color and taste of sake. Iron and manganese can darken sake while also tampering with the aroma. Conversely, minerals like potassium and magnesium help propagate yeast growth and aid the duration of fermentation.

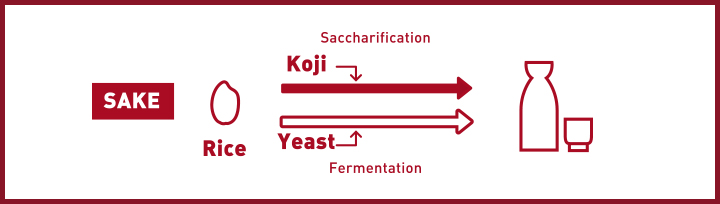

Sake brewing begins with polishing harvested rice to remove the desired amount of bran from the grain. Brewers then wash, soak, and steam the rice before dividing the portions for main brewing and koji production. Koji, the specific strain of mold used in sake production, then propagates in the rice, converting starches into sugars. A small portion of steamed rice, koji, water, and yeast then creates a yeast starter called the shubo. Once the yeast grows enough, increased volumes of rice, water, and koji are added to the mix. This mixture then ferments for several weeks. Brewers then press the mixture to extract sake for filtering.

The fermentation process found in sake production is multiple parallel fermentation. During this process, the koji mixture continues to break down starches into sugars while the yeast simultaneously converts these sugars into ethyl alcohol. This differs from multiple sequential fermentation, in which starches break down to sugars completely before fermentation like a beer.

When the fermentation is completed, sake is separated from the undissolved rice, koji and yeast. After this racking process, most sake undergoes pasteurization before aging. Pasteurization not only sterilizes sake, but also renders any remaining enzymes inactive.

The flavor of sake primarily comes from the rice used in production. Starch and protein present in the rice strain break down throughout the brewing process. Starches become oligosaccharides and glucose. These sugars convert into alcohol, but some remain in the final product. On the other hand, the protein in rice becomes peptides and amino acids, which influence the umami taste in sake. Furthermore, the sugars and amino acids are transformed into aroma compounds through the activity of the yeast.

There are few aroma sources in rice. However, different elements of the brewing process have greater influence on the resulting aroma. The strain of yeast used in fermentation also greatly influences sake aroma. Different strains can carry sweet, fruity, or floral fragrances. As a result, brewers select strains of yeast for aroma properties. But, a well-made koji is necessary for this yeast to reach its full potential. As a result, many breweries focus on koji-making and make koji in house.

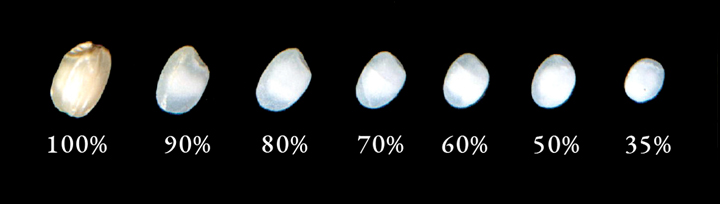

The term “seimaibuai” refers to the degree brewers mill and polish rice grains. It is expressed by a percentage of the weight of milled rice over its original, unmilled weight. Seimaibuai directly correlates to sake variety and can indicate higher quality levels. Additionally, a higher level of polishing results in a more delicate rice grain, which can cause brewers to adjust their brewing technique to achieve desired results.

In Japan, each region has its own designated varieties of sake rice. Well-known varieties include Yamadanishiki, Gohyakumangoku, Miyamanishiki, and Omachi. These sake rice grains are large and have a white core, called shinpaku. This characteristic white, opaque section at the center of the rice kernel is formed by a matrix of starch granules pocked with voids. These sake rice varieties also have a low protein content. Solubility levels and other features of sake rice differ by variety, and these differences are reflected in the flavor characteristics of sake.

Sake occupies a special place in Japanese culture. Not just a beverage, the drink represents a closeness with Shinto gods and within the community. As a result, the production method and taste profile of sake often reflect the area around it. This appears in the tendency of breweries to produce sake with similar flavors in the same area. While these breweries will share access to water resources, rice selection, koji production, and yeast preference are up to the brewer’s discretion. Instead, these similarities reflect a shared preference and consumer influence on sake flavor.

This sense of locality provides the opportunity for distinction based on regionality. As brewing technology advances, it allows brewers more influence to customize sake flavor. This customization could lead to more distinct sake varieties reflecting the culture of its production region.

The most defining traits of sake ultimately come from the brewing method. Seimaibuai determines the sake variety, creating categories like honjozo and ginjo sake. When creating a certain variety, brewers then adjust their methods to address the brewing requirements of polished rice and ensure higher quality sake. The yeast strain selected changes the aroma and the degree of koji production can render sake sweet or dry. Because of the enzymatic power of koji, it is also important to determine whether or not to employ pasteurization. This gives the brewer considerable control over the final product rather than simply working with natural conditions.

As brewing techniques continue to advance, more varieties of sake emerge. The emergence of sparkling sake and aged sake reflect how brewers can match popular trends. New varieties also translate to developing a more defined class system within the sake community. This gives higher priority to brewing technology and method than resources in establishing a quality and luxury sake.

| Sake | Wine |

| The brewing techniques used greatly impact the resulting sake. | The variety of grapes used and growing conditions affect the resulting wine. |

| Seimaibuai plays a great role in determining sake variety and indicating quality. | Grape harvest yield determines wine quality. |

| Consistent brewing methods produce sake of consistent quality year to year. | The year grapes are harvested affects the wine due to changing conditions year to year. |

| In addition to rice, water, and environment, taste preference, and local tradition shape regional differences. | Soil, topology, and climate influence characteristic flavors of regional variations. |

| The freshness of sake is vitally important, so aging is carefully moderated. But, some sake is aged several years. | Most wine doesn’t undergo much aging. Only high-quality, premium wines experience long-term aging. |

While sake and wine differ greatly in composition and production, they do share several similarities. Both drinks can pair with food to enhance the taste and overall experience of a dish. At the same time, wine and sake have many of the same flavor and aroma classifications considered for individual quality assessment. Experts on both sake and wine must undergo extensive training on the production process and flavor assessment before earning their credentials. With emerging regional distinction in the sake industry, sake and wine are growing more similar, almost like cultural counterparts to one another.

While often conflated, wine and sake have several distinctions that make each drink enjoyable and unique. Wine may currently have more global notoriety, the similar traits of sake can provide the Japanese beverage with more exposure through comparison. With more accessibility and education, sake could hold a place on drink menus alongside wine rather than existing as a subcategory within it.