Main Mash (moromi)

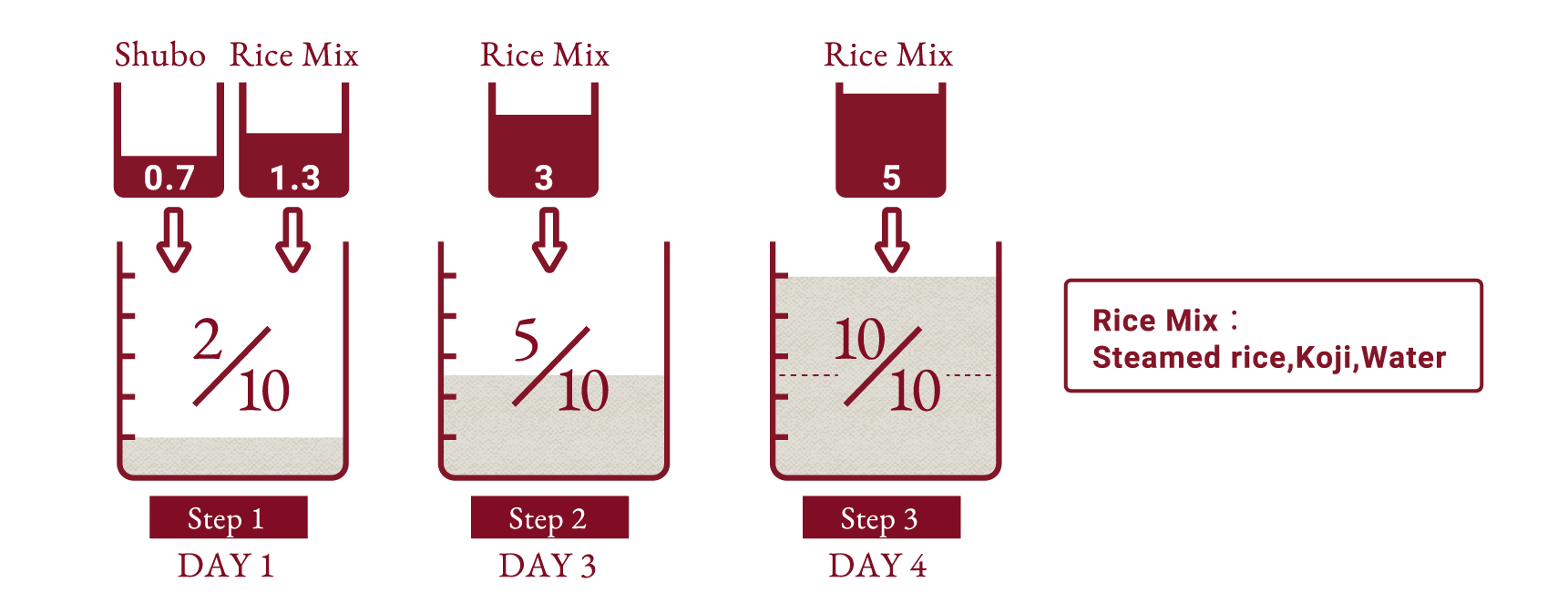

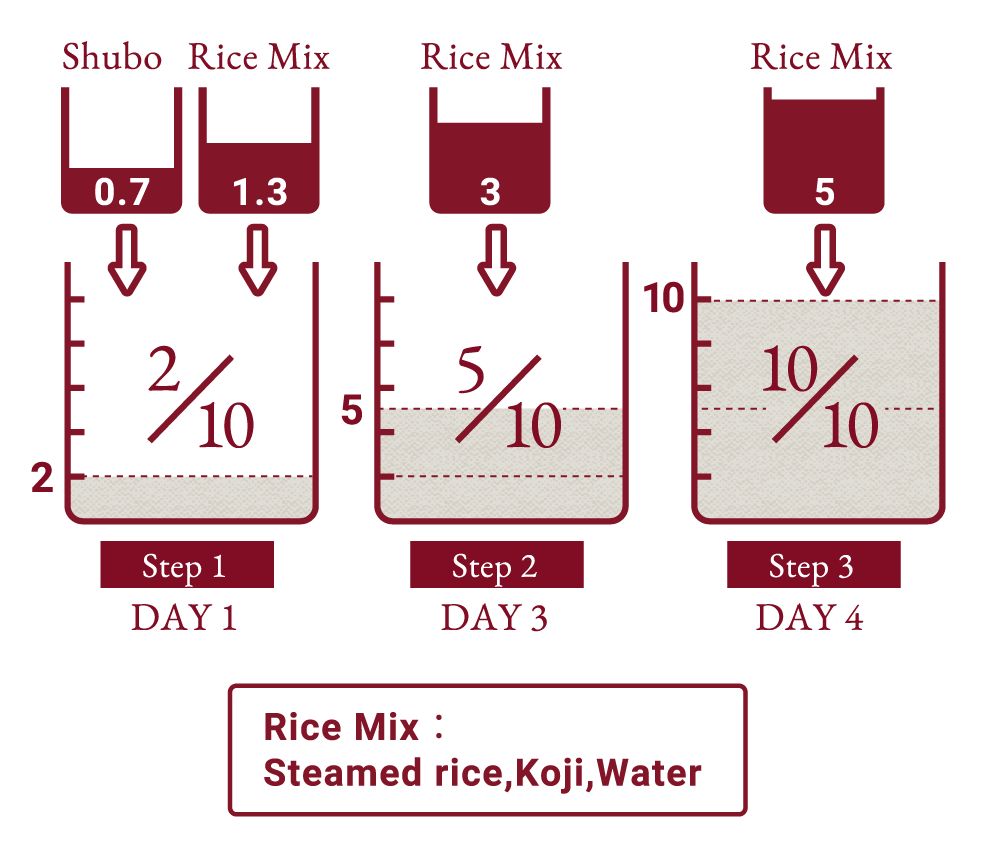

3-Step Fermentation

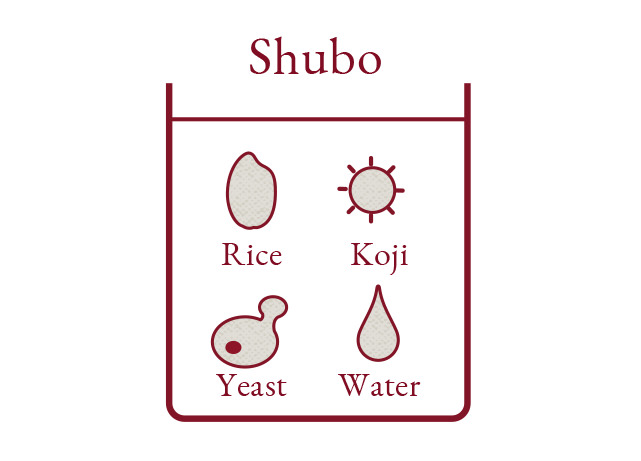

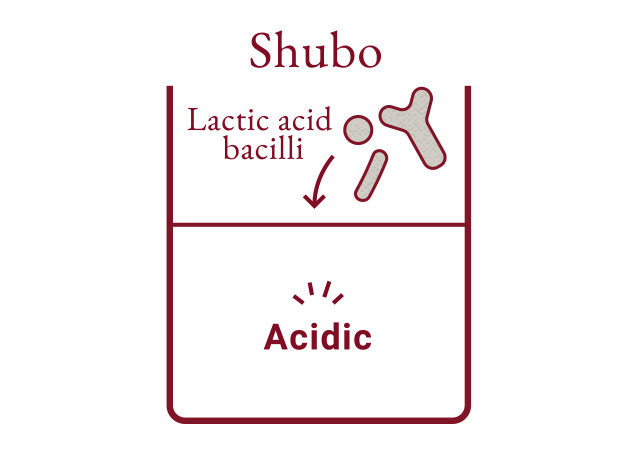

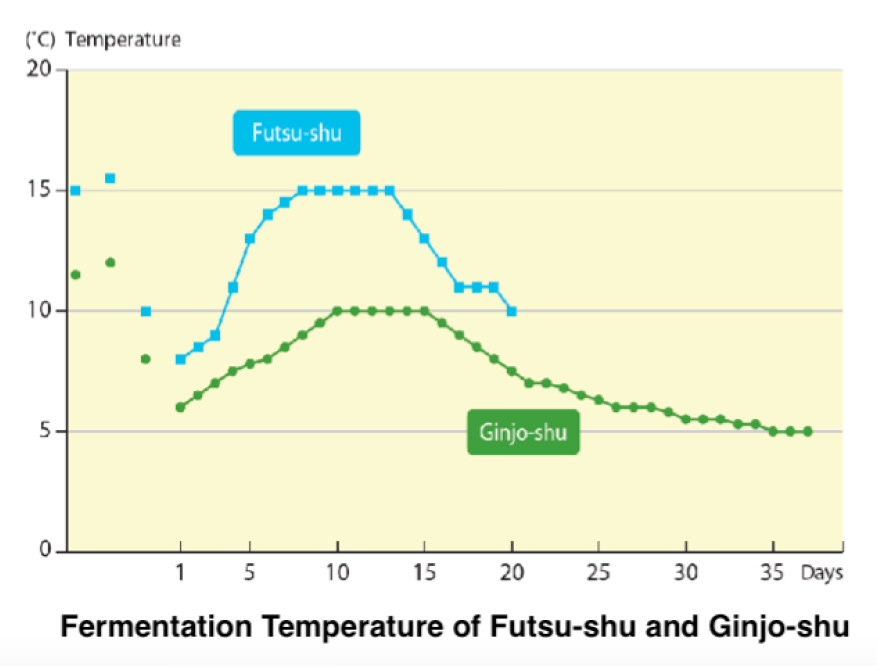

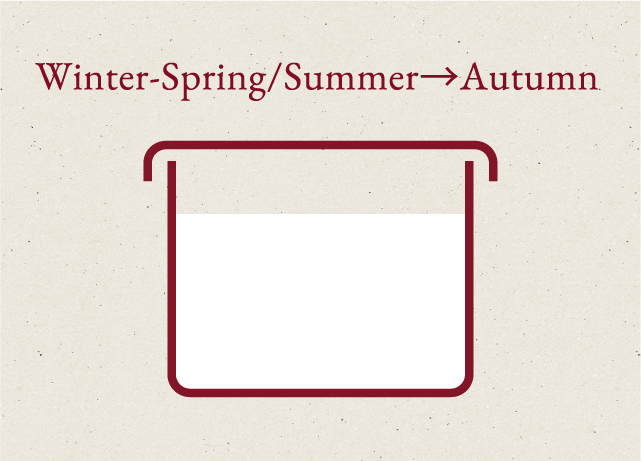

The fermentation process in sake brewing usually consists of three successive steps, known as sandan jikomi in Japanese. In the first step, a mix of shubo (source of yeast), steamed rice, koji, and water sit in a tank and ferment over a day. Then, brewers add a batch of steamed rice, koji, and water two more times to gradually increase the fermenting mash volume. Through this process, the growth of yeast to mash is well balanced and the active fermentation produces enough alcohol in the mash to prevent any microbial contamination. During the fermentation processes, the mash temperature stays between 8℃ to 18℃. These three steps occur over a period of three to four weeks.

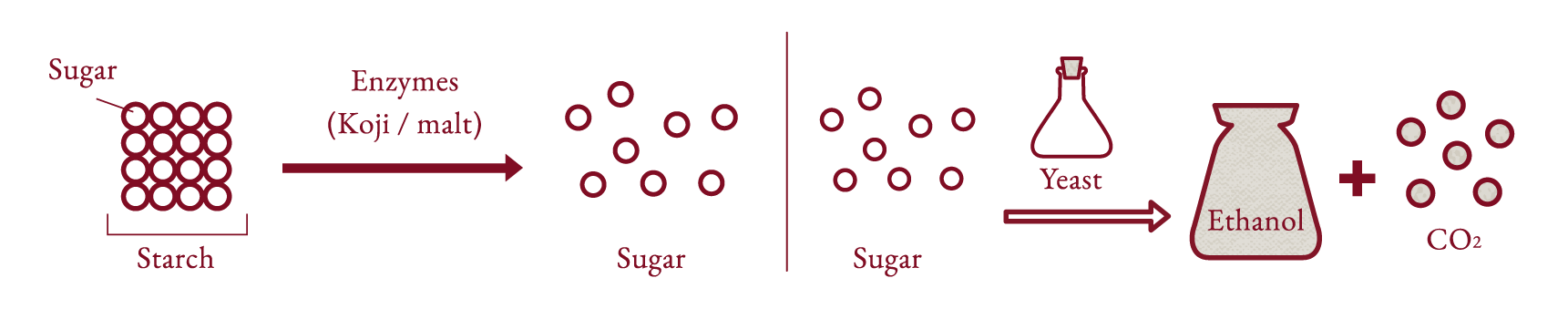

Saccharification and Alcoholic Fermentation

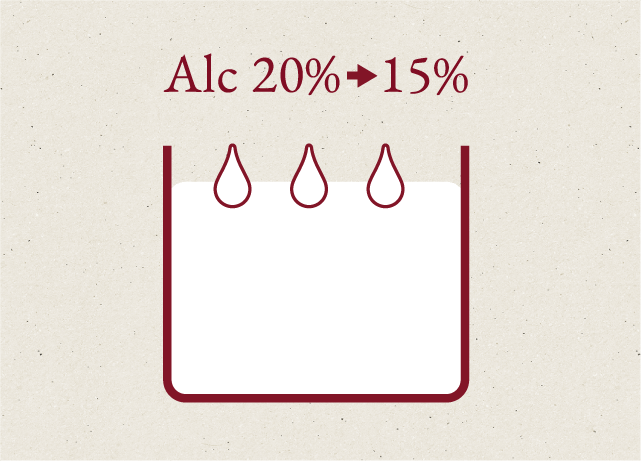

In sake mash, two processes take place at the same time; koji’s diastatic enzymes break down rice starch into sugar, and the yeast ferments the sugar into alcohol. Sake mash is very dense and the ratio of water compared to the polished rice is roughly 1.3. If all the rice starch changes to sugar at once, the extract shows about 35 g/L, which is too high for yeast to thrive. However, since the sugar is fermented into alcohol as it gets produced, the mash's sugar concentration stays at an ideal level. Therefore, these parallel processes, together with the 3-step fermentation, actively support an efficient fermentation activity, producing a 17 to 20% alcoholic content by the end.

Addition of Neutral Spirits

At the last stage of the fermentation process, brewers are allowed to add a small amount of neutral spirits, or jozo-alcohol in Japanese, to the mash. By doing so, the spirits extract the aromatic components, especially esters, and dilutes the acidity and amino acids to make the flavor lighter. The resulting sake tends to be smooth and easy to drink. Neutral spirits are made from molasses and/or grains and diluted to about 30% alcohol before addition. For specially designated sakes (ginjo, daiginjo, honjozo, and tokubetsu honjozo), the amount of its use is limited to less than 10% of the polished rice weight used for brewing. Junmai is the only type of sake that has no addition of neutral spirits. Therefore, any sake in the junmai category is free of neutral spirits.