Ancient Times:

The Earliest Record

~2nd century BC

Rice and the brewing technique brought in from China

3rd century AD

The first record mentioning the existence of sake in Japan

Read Full HistoryJapan Sake and Shochu Makers Association | JSS

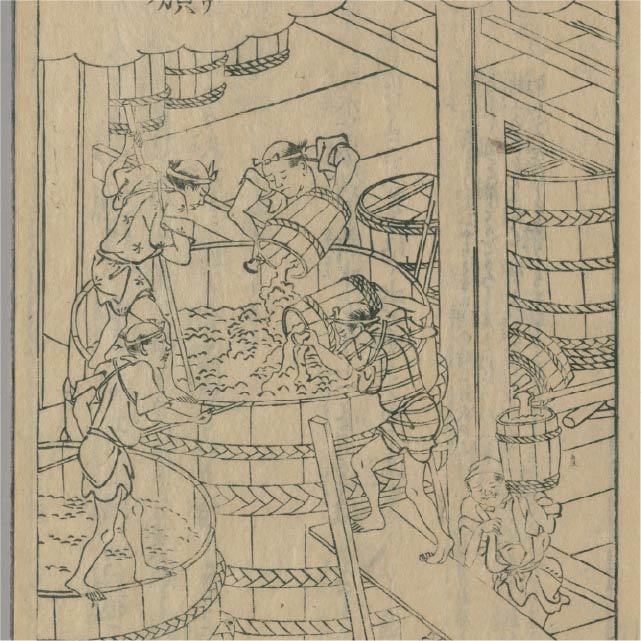

The technique to ferment rice into an alcoholic drink was developed in ancient China. It arrived in Japan along with rice cultivation around 2500 years ago. Since then, Japanese people continuously refined production methods to create a truly unique drink called sake. Here is a detailed outline of the history of sake, from the early beginnings to developments in the modern era.

Rice and the brewing technique brought in from China

The first record mentioning the existence of sake in Japan

Read Full History

Sake brewing division established in the Imperial Court

First record of sake brewing using mold (koji)

Sake brewing method documented in the code of practice

Read Full History

Record of religious institutions making sake

Read Full History

Record of 342 sake-related businesses in Kyoto

First record of pasteurization in sake production

Read Full History

Itami became a star sake producer.

A technical book for sake brewers was written

Government record shows 27,251 brewers across the country

Discovery of miyamizu (water ideal for sake making) in Nishinomiya, bringing sake production there

Read Full History

First export of sake

First bottling of sake

Identification of sake yeast, Saccharomyces sake YABE

Establishment of the National Research Institute of Brewing (NRIB)

First Annual Japan Sake Award by NRIB

War-related food shortages limited the production of sake

The grading system of sake was enforced by the government (terminated in 1992)

Read Full History

Increase in trend of ginjo-shu and unpasteurized sake

Enforcement of "Sake brewing quality labeling standards", a new system to categorize sake by the production method

The amount of sake production starts to decline

Increase in export and the production of specially designated sake in proportion, and a new take on regionality

Read Full History